Home | About | About Autism

Page Disclaimer: This page contains numerous quoted sections and links to other websites, articles, and organizations managed, written, and led by autistic people. The intention of this page is to provide visitors with a starting point for learning more about autism. The best way to learn about autism is to listen to autistic people. Commonwealth Autism stands with the people we serve, so we use identity-first language (autistic, disabled) as an organization and respect autistic individuals who prefer person-first (has autism, has a disability).

What is Autism?

Autism is a developmental disability that affects how people experience the world around them. Autistic people are born autistic and will be autistic for their entire life. Anyone can be autistic, regardless of race, ethnicity, gender, or age.

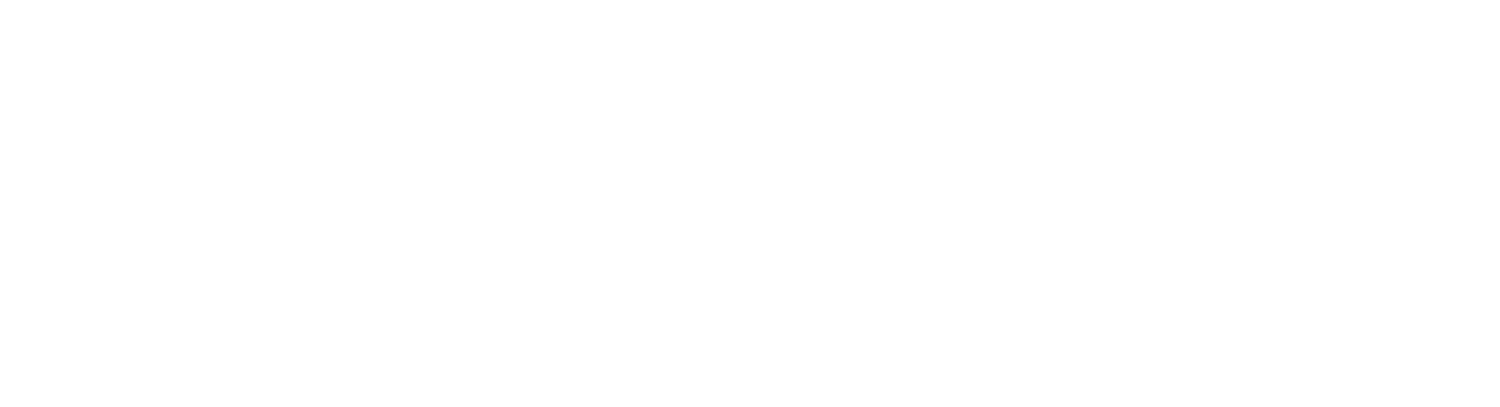

Autism is not a spectrum in terms of a straight line, instead, it is a collection of traits, and different autistic people have different support needs in each area. Rebecca Burgess’ illustration offers a better understanding of the spectrum:

Understanding Autism: A Commonwealth Autism Perspective

At Commonwealth Autism, we believe in meeting every autistic individual where they are. There is no one way to be autistic, and no single approach fits all. We strive to build a Virginia where all autistic people have equitable access to support, opportunity, and inclusion in every part of their lives.

Drawing from the values of self-advocacy and community empowerment—as also expressed by organizations like the Autistic Self Advocacy Network (ASAN)—we recognize the diversity within the autism spectrum. Autistic individuals may speak or use alternative forms of communication. They may require different levels of support throughout their lives. Some live independently, while others thrive with more structured assistance. All of these experiences are valid. Every autistic person contributes meaningfully to their communities and deserves understanding, acceptance, and choice.

There Are Many Ways to Be Autistic

Autism is a neurological and developmental difference that affects how people think, feel, move, communicate, and relate to others. While every autistic person is unique, many experience some common traits:

Thinking Differently

Autistic people often have deep passions and interests. Some may hyper-focus on subjects that others overlook, displaying incredible depth of knowledge and creativity. At the same time, challenges with executive functioning—like organizing, planning, or task switching—may arise. These are not deficits, but differences in how the brain processes information. Commonwealth Autism incoporates strategies to support these differences, fostering strengths and reducing barriers.

Processing Change and Overwhelm

Predictability and routine often help autistic individuals feel safe and regulated. Surprises or unexpected changes can be distressing and may lead to emotional or physical overwhelm. Our programs prioritize structure and visual supports to reduce anxiety and support transitions.

Sensory Processing

Many autistic people process sensory input in unique ways. They may be highly sensitive to lights, sounds, or textures, or may seek sensory input to regulate themselves. Stimming—repetitive movements or sounds like rocking, humming, or hand-flapping—is one way autistic individuals self-soothe and process sensory information.

In Life Skills and Career Readiness programs, we create sensory-aware environments that help individuals focus, thrive, and feel secure.

Movement and Speech

Motor planning challenges can affect how someone starts or stops movement, speaks, or manages fine motor skills. Communication may involve spoken language, scripted responses, or Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) tools like letterboards or iPads. At Commonwealth Autism, we support all forms of communication. Everyone has a voice—whether verbal, behavioral, or assistive.

Social Communication

Autistic people may communicate or interpret social cues differently. They may avoid eye contact, use direct language, or not pick up on others’ emotions in expected ways. This doesn’t mean they lack empathy. In fact, many autistic individuals are deeply sensitive to others’ feelings. In our preschool inclusion work and adult transition programs, we train others to understand and adapt to neurodivergent communication styles, fostering authentic connection.

Support with Daily Living

Living in a world built for non-autistic people can be exhausting. Some autistic individuals may need support with daily tasks like cooking, transportation, employment, or healthcare. Others may be independent in some areas but need help in others. Our programs adapt to this reality, offering flexible, personalized supports that build confidence and practical skills.

Words Matter: Rethinking Functioning Labels

We avoid terms like “high-functioning” or “low-functioning.” These labels are not only vague but can also be demeaning and misleading. They reduce complex individuals to binary categories, ignoring both their strengths and support needs. At Commonwealth Autism, we speak about individuals as they are: with talents, needs, and preferences. This ensures people get the support they require without assumptions limiting their choices.

As ASAN puts it:

“Functioning labels aren’t a good way to think about autism. We all have things we are good at and things we need help with. Using functioning labels makes it harder for us to get the help we need, and for us to make the choices we want. Instead, we should talk about people as individuals. Talk about what someone is good at, and what they need help with. This makes sure we can get what we need.”

Our Commitment to Inclusive Support

At Commonwealth Autism, our mission is to unlock opportunities so every autistic individual can achieve their full potential. Whether through our Career Readiness & Employment program, our Life Skills coaching, or our statewide resources and partnerships, we center neurodivergent voices in everything we do.

We build systems and services that:

- Respect individual communication and sensory needs

- Support different learning styles and developmental paths

- Challenge stigma and outdated assumptions

- Create real, inclusive opportunities across the lifespan

We believe in a Virginia where autistic individuals are not just supported—but welcomed, empowered, and celebrated.

.

Early Signs of Autism

Children can be diagnosed as autistic when they’re young, some as early as 15 months. Not everyone is diagnosed early in life as it’s quite common for a child to not be diagnosed until they are older or even an adult, especially if they are a girl, a person of color, and/or do not have an accompanying learning disability.

Some signs that a child may be on the autism spectrum include:

- Not drawing their parents’ or others’ attention to objects or events, for example not pointing at a toy or book, or at something that is happening nearby (or a child may eventually do this, but later than expected)

- Carrying out activities in a repetitive way, for example always playing the same game in the same way, or repeatedly lining up toys in a particular order

- May strongly prefer routines, predictability, and repetition

- Emerging difficulties with social interaction and social communication

- Stimming: tapping, humming, pacing, rocking back and forth, repetitive movements

- Behavior such as biting, pinching, kicking, pica (putting inedible items in the mouth), or self-injurious behavior

- Decreased babbling or use of language

You can learn more about typical developmental milestones on this timeline provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

If you believe your child has autistic characteristics, contact your pediatrician, and they will make the appropriate referrals based on the findings of their initial assessment.

Do you or your loved one display autistic characteristics?

Find out for sure.

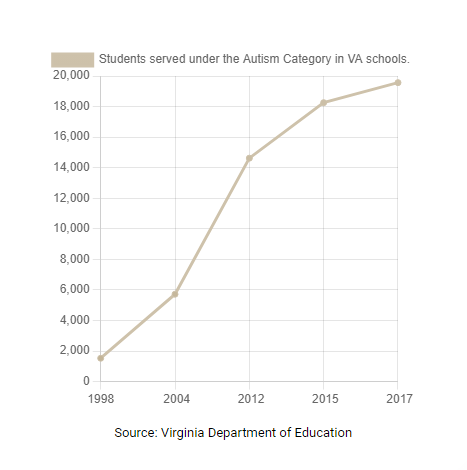

Prevalence

According to the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network’s 2025 report, which reflects data from the 2022 surveillance period, approximately 1 in 31 eight-year-old children have been identified as autistic.

- Among 8-year-old children, autism was 3.4 times as prevalent among boys than girls.

- Among 8-year-old children identified as autistic with available IQ scores, over one-third (39.6%) were also classified as having an intellectual disability.

- One study estimates that in the United States, approximately 1 in 45 adults between the ages of 18 and 84 years is autistic.

ASAN published a statement addressing the latest ADDM Network report–see the full statement here:

“ASAN is not surprised to see the diagnosis rate increase. We believe, as the report explains, this increase reflects better recognition and diagnosis of autism across the U.S. We know that many disparities in diagnosis have become smaller.

For the second year in a row, Non-Hispanic white children had the lowest diagnosis rate of any race or ethnicity at most sites. The report explains that a lot of researchers, doctors, and policymakers have worked hard to improve access to screening and diagnostic services for underserved groups. The increases in diagnosis for non-white groups is proof that this work is helping. The report found that there are still some disparities. Higher income is related to a higher diagnosis rate for Black, Hispanic, and Asian and Pacific Islander children, but not for white children. This shows that there is still more to be done to make sure all children have access to screening.”

.

Diagnosis

Although autism can be diagnosed as early as 15-18 months of age, the average age of diagnosis remains between 51 and 53 months, with some individuals not recognized until adulthood. According to the 2025 ADDM Report, more children born in 2018 were identified as autistic by 48 months of age compared to those born in 2014, indicating a continued trend toward earlier identification. One study found that autistic children face a delay of over two years between initial developmental screening and receiving a formal diagnosis, despite progress in early screening efforts.

The following is ASAN’s statement regarding seeking a formal diagnosis (found under “The Autistic Community” topic section):

“Whether an autistic person has an autism diagnosis from a doctor or not, they are still a part of the autistic community. It can be really hard to get an autism diagnosis, especially for people of color, women and girls, trans and nonbinary people, and people who figured out they are autistic when they were an adult. It can cost a lot of money, or a doctor may have the wrong ideas about autism and not want to give someone a diagnosis. Some people just don’t want a diagnosis, and that is okay, too. When ASAN says “the autistic community”, we include everyone, whether they have a diagnosis or not.”

Screening

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that all children be screened for autism at ages 18 and 24 months, along with regular developmental surveillance. If you are not sure whether your pediatrician screens for autism, ask. During a screening, the pediatrician observes the child’s behavior and development. The doctor may also ask the child’s caregiver to complete a questionnaire. If the doctor notices atypical or delayed development, they may recommend a comprehensive diagnostic assessment.

Once your doctor submits a referral, you may have to wait before you actually go for the assessment. In the meantime, your child could be referred to other teams such as speech therapy, occupational therapy, or education support services.

Medical Diagnosis

Various experts can make this diagnosis, including some psychologists, pediatricians, and neurologists. Psychologists are often involved in the diagnostic process. It is important that the expert making the diagnosis has extensive experience working with the wide range of characteristics associated with autism. The diagnostician should explain to you the reason for each test or assessment. You should be given plenty of time to ask questions. Don’t be afraid to ask for explanations or clarification if you need them.

To make a diagnosis of autism, diagnosticians draw on a number of sources of information:

- Patient interviews

- Observations in more than one setting

- Tests of cognitive and language abilities

- Medical tests to rule out other conditions

- Interviews with caregivers, teachers, or other adults who can answer questions about the patient’s social, emotional, and behavioral development

The current diagnostic criteria in the DSM-5 are not all-inclusive of autistic characteristics observed in girls, women, nonbinary people, people of color, and those who do not have an intellectual disability. Brian Reichow and Fred Volkmar discuss the narrowing of the autism diagnostic criteria in the DSM-5 here.

The Diagnostic Report

The diagnostician will tell you whether or not they think your child is autistic. They might do this on the day of the assessment (rarely), by phone on a later date, or in a written report that they send to you. Diagnostic reports can be difficult to read and understand in some places. You can call the diagnostician to talk through any parts of the report that you do not understand. Diagnostic reports are also very deficit-based, detailing what the child cannot do, which can be upsetting for caregivers to read.

The report should give a clear diagnosis. Phrases such as “has autistic tendencies” are not very helpful because they imply that a child is not autistic. This can cause problems when trying to access autism-specific support. It is very important to understand your child’s individual profile of needs. The report may say that your child presents a particular autism profile and may give recommendations for support.

Source: National Autistic Society

Some people may present characteristics associated with Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA). PDA is also known as Persistent Drive for Autonomy. PDA is not clinically recognized, so some people are diagnosed as autistic with a PDA profile. The PDA Society describes autistic demand avoidance as:

“Autistic people may avoid demands or situations that trigger anxiety or sensory overload, disrupt routines, involve transitioning from one activity to another, and activities/events that they don’t see the point of or have any interest in.

They may refuse, withdraw, ‘shutdown’ or escape in order to avoid these things.

Helpful approaches include addressing sensory issues, helping individuals adjust to new situations (for instance by using visuals or social stories), keeping to a predictable routine, giving plenty of notice about any changes or accepting that avoiding some things is perfectly acceptable.”

Educational Diagnosis

Just because your child receives a medical diagnosis of autism does not mean they will automatically receive the educational disability category of autism. This means your child may not be immediately eligible for special education services through the public school system. Not all autistic individuals need additional supports at school but some may have an Individualized Education Program (IEP) or 504 Plan. Contact your local school division’s special education department to request an assessment to obtain an educational diagnosis.

Individualized Education Program (IEP) meetings can be very intimidating for caregivers and for autistic students. Students often feel like the IEP meeting is when teachers and other professionals will only mention what the student needs to improve upon, instead of what the student is doing well. Far too often, IEP meetings are led from a deficit-based approach instead of a strengths-based one. Rachel Dorsey, Hilary Crow, and Caroline Gaddy share the importance of valuing autistic attributes in this ASHA LeaderLive article.

Caregivers may want to seek the assistance of a Special Education Advocate to ensure their child is receiving the educational services they are entitled to. Lisa Wright, an IEP Special Education Coach, shares free IEP tips and resources for caregivers on her social media.

Some caregivers of autistic children report that their child has “behavioral issues” at school. Oftentimes, a child “acts out” because they have no other way to communicate, need additional support in the classroom, or are experiencing distressing sensory overload. Talk to your child’s education team about your concerns. Autism Level UP! provides free resources for caregivers and educators to use in the classroom, at home, or anywhere for autistic students.

For more information, refer to The Virginia Family’s Guide to Special Education and the autism page on the VDOE’s website. ASAN has a comprehensive list of resources and information regarding your educational rights that can be found here.

Therapy & Additional Services

The best practice when it comes to autism is focusing on supporting autistic people to live good lives and advocate for themselves. Autistic children do not need therapy simply because they are autistic.

“ASAN does not support any one kind of therapy for autistic people. Different things will work better for different autistic people. The most important thing is that any therapy should help autistic people get what we want and need, not what other people think we need. Good therapies focus on helping us figure out our goals, and work with us to achieve them.”

There are numerous evidence-based therapies that can be helpful for autistic people, such as occupational therapy, speech therapy, physical therapy, Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC), Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), music therapy, play therapy, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), and many more.

Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA) is one of the most commonly implemented services for autistic children and often the first suggestion for caregivers. ABA seeks to understand, predict, and change behavior and is delivered in a variety of settings, including home, school, clinic, and other community settings. ABA is a controversial practice due to the profession’s previous use of negative reinforcement strategies and the correlation between those exposed to ABA practices and PTSD symptoms. Not all ABA therapists are the same, and there is a growing number of ABA therapists, even some autistic ABA therapists, who are actively trying to rebrand and reframe ABA. David Meer wrote an in-depth assessment of the available therapies for autism and explained the controversy surrounding ABA while offering strategies to improve the field:

“Autistic adults are speaking out against this form of therapy, something that you rarely encounter with other treatment modalities. I do not know of many other therapies that have received as much backlash, to the point it is being labeled as abuse and traumatic. Autistic adults are urging us to reconsider how we deliver therapeutic services and the potential long-term consequences. Opponents of applied behavior analysis suggest that it can lead to prompt dependence, individuals who are conditioned to obey without questioning, loss of intrinsic motivation, decrease in self-confidence, and learned helplessness. A growing concern is fear that this form of therapy will exacerbate exposure to violent crime and sexual assault. Further research is needed, but these concerns need to be explored and addressed.

It is equally important not to simply dismiss behavior analysis – it is too valuable a science to ignore. Many of the principles are derived from sound theory and years of empirical research. There is no questioning that operant conditioning is an effective means to change behavior. It is important for us to understand how the environment impacts our thoughts, mood, and behavior. We should understand how sensory input impacts us so we can be prepared. We should understand the impact of operants on our future behavior. Knowledge of these systems can empower us to manage ourselves in response to the world and seek out accommodations as needed.”

When seeking support for your child, ask “What specific needs does my child have?” to determine the best options for them.

The Importance of Early Intervention

Research shows that intervention is most effective in the preschool years when the brain is developing most rapidly. Eligibility for early intervention services is based on evaluating your child’s skills and abilities.

The Infant & Toddler Connection of Virginia is Virginia’s early intervention system for infants and toddlers (age 0-36 months) with disabilities and their families. Any infant or toddler in Virginia who isn’t developing as expected or who has a medical condition that can delay typical development is eligible to receive early intervention supports and services under Part C of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

Early intervention supports and services focus on increasing the child’s participation in family and community activities that are important to the family. In addition, supports and services focus on helping parents and other caregivers know how to find ways to help their children learn during everyday activities.

The Infant & Toddler Connection of Virginia’s supports and services are available to all eligible children and their families regardless of a family’s ability to pay.

What is Neurodiversity?

Nicole Baumer, MD, MEd and Julia Frueh, MD summarize the neurodiversity movement as:

“Neurodiversity describes the idea that people experience and interact with the world around them in many different ways; there is no one “right” way of thinking, learning, and behaving, and differences are not viewed as deficits.

The word neurodiversity refers to the diversity of all people, but it is often used in the context of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), as well as other neurological or developmental conditions such as ADHD or learning disabilities. The neurodiversity movement emerged during the 1990s, aiming to increase acceptance and inclusion of all people while embracing neurological differences. Through online platforms, more and more autistic people were able to connect and form a self-advocacy movement. At the same time, Judy Singer, an Australian sociologist, coined the term neurodiversity to promote equality and inclusion of “neurological minorities.” While it is primarily a social justice movement, neurodiversity research and education is increasingly important in how clinicians view and address certain disabilities and neurological conditions.”

For those new to the subject of neurodiversity, it might be confusing to know what the right words are to use when speaking about the subject.

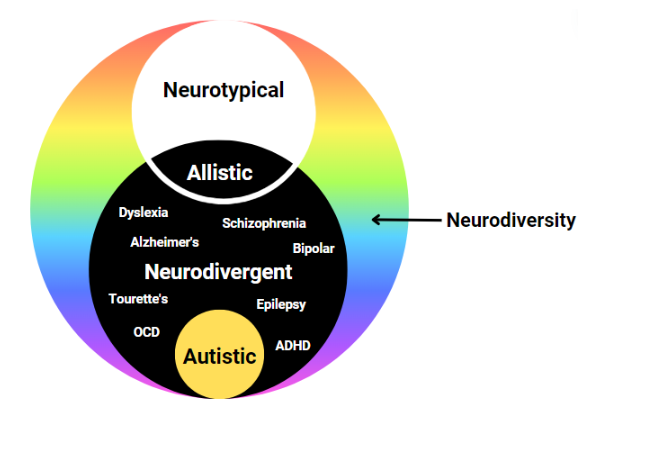

Neurodiversity: The natural diversity of human minds. It is a biological fact that we are diverse in our minds just like we are diverse in our ethnicity, gender, race, sexuality, etc.

Neurodivergent: An umbrella term for individuals who have a mind or brain that diverges from what is typical. It simply means having a mind that functions differently from what is considered the norm including learning, processing, interpreting, feeling, etc. Some examples of neurodivergencies include ADHD, autism, OCD, Alzheimer’s, dyslexia, bipolar, epilepsy, Tourette’s Syndrome, and many more.

Neurotypical: Having a mind or functioning that falls within society’s standards of what is deemed “typical”, “common”, or “normal”.

Neurodiverse: A term to describe a group of individuals who represent the spectrum of neurodiversity, which includes neurotypical and neurodivergent individuals. *Remember, an individual cannot be neurodiverse; however, one individual can be multiply neurodivergent (e.g. someone can be autistic and have OCD). Individuals who aren’t neurotypical would be neurodivergent.

Allistic: People who are not on the autism spectrum, which includes both neurotypical and non-autistic neurodivergent people

Autism Symbols

The rainbow infinity symbol represents neurodiversity–the full spectrum of colors represents the diversity of the autism spectrum as well as the greater neurodiversity movement. The autistic community has adopted the gold infinity symbol because the symbol for gold is AU and gold represents something of high value. There are new and evolving symbols created by autistic artists and activists, such as the colors of the rainbow weaving in motion created by Lori Shayew and Kelly Green. A growing number of autistic people do not prefer the puzzle piece as the symbol of autism.

What is Masking?

Dr. Hannah Belcher is a lecturer, researcher, speaker, and author. Here Hannah discusses masking in autistic people, based on research and her own personal experience.

“To ‘mask’ or to ‘camouflage’ means to hide or disguise parts of oneself in order to better fit in with those around you. It is an unconscious strategy all humans develop whilst growing up in order to connect with those around us.

However, for us autistic folk the strategy is often much more ingrained and harmful to our wellbeing and health. Because our social norms are different to others around us, we often experience greater pressure to hide our true selves and to fit into that non-autistic culture. More often than not, we have to spend our entire lives hiding our traits and trying to fit in, even though the odds of appearing ‘non-autistic’ are against us.

Masking may involve suppressing certain behaviours we find soothing but that others think are ‘weird’, such as stimming or intense interests. It can also mean mimicking the behaviour of those around us, such as copying non-verbal behaviours, and developing complex social scripts to get by in social situations. With this comes a great need to be like others, and to avoid the prejudice and judgement that comes with being ‘different’.

Over time we may become more aware of our own masking, but it often begins as an unconscious response to social trauma before we even grasp our differences. I was 23 when I received my autism diagnosis, and it was only through learning more about masking that I realised how my diagnosis had been hidden for so long. It wasn’t that my autistic traits weren’t there, they’d just been in disguise for so long.

The strategy of masking shows just how clever and resourceful our young minds are at finding ways of coping. At some points in our lives, like during job interviews, it may have even be useful.”

Neurodiversity-Affirming Therapists

A neurodiversity-affirming therapist understands individual neurotypes have unique strengths, needs, and challenges and are not problems to be cured or solved. The neurodiversity movement shifts away from the medical model’s idea that neurodivergent people are “disordered.” Rachel Dorsey explains what strengths-based therapy really means here.

It can be difficult to find the right therapist whose values align with your own. This article from MACS PLLC provides a list of questions to ask a potential therapist to help determine if they are the right fit. There are neurodiversity-affirming therapist directories that can be found on Learn Play Thrive, Therapist Neurodiversity Collective, Inclusive Therapists, Neurodivergent Therapists, and Neurodivergent Practitioners Directory.

Avoiding Misinformation

It’s important to note that there is a lot of misinformation about autism on the internet and elsewhere. At best, this misinformation is confusing, and at worst, it can be harmful. We recommend the following resources to those interested in learning more about autism:

The Cost of Services

In Virginia, there are several ways to pay for services:

- Public funding: Early intervention, FAPE (Free Appropriate Public Education)

- Private insurance: As of January 2020, Virginia law mandates that state-regulated large group plans cover medically necessary care for autistic people, regardless of age

- Medicaid or a Medicaid Developmental Disability Waiver

- Commonwealth Coordinated Care Plus (CCC Plus) Waiver

- 529 ABLE (529A) accounts

- Out-of-pocket/private pay

Your Rights

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) is a federal law that ensures services to children with disabilities. IDEA governs how states and public agencies provide early intervention services (for ages birth to three) and special education and related services (for ages 3-21).

Free, Appropriate Public Education (FAPE)

Remember, just because your child has a medical diagnosis of autism does not mean they’ll automatically receive the educational disability category of autism. If your child does receive an educational diagnosis of autism, their Individualized Education Plan (IEP) team decides whether your local school division can provide FAPE. If it can’t, the state will pay for out-of-school placement. For more information regarding placement decisions, read The Virginia Family’s Guide to Special Education.

Learn More from Autistic and Allistic Advocates

The following are listed in no particular order:

9221 Forest Hill Ave, Richmond, VA 23235

(804) 355-0300

FACT Autism Resource Center- 3509 Virginia Beach Blvd, Virginia Beach, VA 23452

CA works with autistic people and their families to help them thrive. Every day, we’re building a future where the most vulnerable Virginians can actively participate in our community and realize their full potential.

Read our recent blog posts: